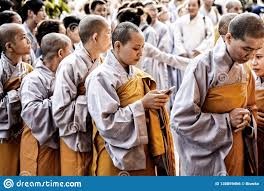

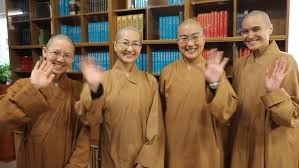

All About Buddhist Nuns

Buddhism has evolved during more than 2,000 years in many different Asian countries (including India, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Myanmar, China, Korea, Japan, and Tibet). At times Buddhist nuns had a prominent and respected role and at other times they vanished into obscurity. This article will endeavor to explain why there exist such diverse types of Buddhist nuns with different statuses, robes, and cultures.

|

|

|

|

Two thousand five hundred years ago in India, Buddhist women shaved their heads, donned saffron robes, and became celibate nuns. They aspired to awakening, meditated, and taught lay followers. Their precepts forbade them to touch money, and thus they depended on alms for their support. The nuns' accomplishments and awakening experiences are recounted in the Therīgāthā (Psalms of the Sisters ), seventy-three poems expressing the spiritual search and struggles of the first Buddhist nuns, which had been orally transmitted until they were written down six hundred years later, and the Apadāna (collection of moral biographies) composed in the second and first-century BCE, which contains forty biographies of eminent early nuns.

The order of Buddhist nuns (bhikṣuṇī ) began later than the monks' order (bhikṣu ). As tradition has it, the Buddha at first seemed reluctant to give ordination to his female followers. His attendant, Ananda, pointed out that because the Buddha agreed that men and women were equal in their capacities for spiritual attainment, it seemed only equitable to let women enter his order of mendicants. Ananda was moved by the distress and spiritual aspiration of the Buddha's foster mother and aunt, Mahāpajāpatī, and of the many women in her entourage. They became the first Buddhist nuns. According to tradition, the Buddha gave eight extra rules to the nuns for entering the homeless life:

- A nun who has been ordained for a century must bow to a monk who has been ordained for a day.

- A nun must not spend the meditation season (vassa, i.e., the monsoon period) in a place where there are no monks.

- Every fifteen days, the nuns must ask the monks for the date of the observance day, and must ask them to give the nuns a teaching.

- After the meditation season a nun must tell her faults to both the order of monks and the order of nuns.

- If a nun commits a grave error she must submit herself to the scrutiny of both orders for fifteen days.

- A nun can obtain full ordination from both orders only after she has observed the six precepts during two years as a postulant.

- A nun must never scold a monk.

- The nuns cannot teach the monks, but the monks can teach the nuns.

As with the monks' order, a vinaya (rule of discipline) was developed for the Buddhist nuns' order in which their precepts were collected. After the death of the Buddha, different schools developed their own vinayas. Today, the Theravāda Vinaya, which contains 227 precepts for monks and 311 for nuns, is followed by the monastics in Southeast Asia (Thailand, Sri Lanka, and Burma [now Myanmar]); the Dharmagupta Vinaya, which contains 250 precepts for monks and 348 for nuns, by those in Northeast Asia (China, Korea, and Vietnam); and the Mūla-Sarvāstivāda Vinaya, with 253 precepts for monks and 364 for nuns, by those following the Tibetan tradition. Some scholars account for the greater number of precepts for nuns by the fact that the relevant monks' precepts were the starting point for the nuns' list. Specific rules relating to the nuns' situation were then added.

Tibetan Nuns

|

When Buddhism came to Tibet in the seventh century ce the higher ordination for nuns was not transmitted: women were only able to receive ten precepts from fully ordained monks and become novices. Tibetan nuns still take ten precepts, which are subdivided into thirty-six. In 1959 there were 618 nunneries with 12,398 nuns in Tibet, but they suffered greatly during the Chinese Communist takeover and Cultural Revolution. A few nunneries can still be found in Tibet, and some nuns still practice as hermits in caves, but their circumstances are very difficult. There are nunneries in the border regions of Tibet (Ladakh, Nepal, Sikkim, Bhutan), but the social position of nuns is often quite low and sometimes they have to serve menially the monks or even their own families. To remedy this situation, training nunneries have been built in Dharamsala, the residence-in-exile of the Dalai Lama, and other places in northern India. For example, the English nun Tenzin Palmo, who was a hermit in the Himalayas for ten years, has started a nunnery for women from the Indian border regions to train, study, and practice like the monks.

In the West there are an increasing number of Western nuns (more than 300) in the Tibetan tradition. Several nuneries have been establish to providea place where they canlive andpracice together.. One of them isDhagpo Kundrel Ling, a Tibetan Buddhist training center in France, dedicated to three years' retreats and monastic life. In November 2004 ten of the fifty women who became nuns for the duration of the traditional three years' retreat joined thirty other nuns living in a hermitage for nuns with a life-long commitment. These nuns follow a rigorous training but also participate in the life of the center and teach worldwide.

International Outreach

The first International Conference on Buddhist Nuns took place in 1987 in Bodh Gayā, India. At the end of this conference, the international Buddhist women's association Sakyadhita (Daughters of the Buddha) was created. Its objectives were to create a network for Buddhist women around the world, to educate women as teachers of Buddhism, to conduct research on women and Buddhism, and to work for the establishment of the bhikṣuṇī saṃgha where it does not currently exist. Sakyadhita has been instrumental in the reestablishment of the higher ordination in Sri Lanka. Since 1991, Sakyadhita has organized international conferences on Buddhist women every two years in various Asian countries (Thailand, Sri Lanka, India, Cambodia, Nepal). There has also been one North American conference. Most of the conferences are situated in Asia to enable Asian women and nuns to participate in greater numbers and to support Buddhist nuns by bringing highly educated and respected bhikṣuṇī to countries where the position of nuns is low. Often these conferences have stimulated improvements for the nuns in the places visited. They have also helped nuns in isolated situations to make contact and gain support from nuns and women from all over the world. At the conference in Ladakh in 1995, 108 delegates came to this remote part of northern India and met with many Buddhist women from the Himalayan border regions for a conference titled "Women and the Power of Compassion: Survival in the Twenty-First Century."

There is no doubt that the topic of Buddhist nuns has been an underresearched area, but this is slowly changing as contemporary scholars begin to delve into historical and archival materials in Sanskrit, Chinese, and Korean to seek the traces left by Buddhist nuns. It is a search rendered difficult by a patriarchal cultural and religious bias, which have resulted in Buddhist nuns having nearly no place in the lineage, little authority, and no part in the formal hierarchy. Thus they have tended to be omitted in official records. Most of the inscriptions with reference to nuns show them as donors or sponsors of religious festivals.

Because Buddhism is a decentralized religion which has found diverse expressions throughout Asia, Buddhist nuns have been unable to speak in a single voice and with a formalized authority. With the founding of Sakyadhita, Buddhist nuns and women have been able for the first time to meet and support each other and to develop the basis for a nondogmatic authority where diversity is encouraged and Buddhist women and nuns are able to establish their own authority both as individuals and as part of a larger tradition.

Note: This article has been compiled and adapted from other sources for the use of the website.